A US colleague told me about some of the pieces they’ve got planned

next season – Schumann and Beethoven symphonies, Tchaikovsky concertos... Really, I

sometimes think artistic planning consists of taking three spinning wheels

marked ‘overtures’, ‘concertos’ and ‘symphonies’, and spinning the names of the

same two-dozen works in each genre. But it’s got me thinking about a piece I wrote

some years ago.

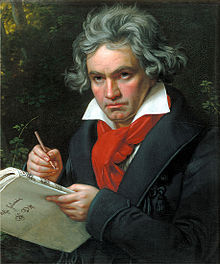

Beethoven’s Ninth was first performed 7 May 1824. In the 188

years since, it has acquired the status of a classic, which means, on one hand,

that it’s been accorded the honour it deserves. On the other, that it inherits

the perennial handicap of a masterpiece: it seems to be set in stone.

Somehow when we hear a work over and over again, we get to

thinking that such a work was always going to turn out the way it did; that it

sprang, like Homer’s Athena, ‘fully armed from the head of Zeus’. Such a belief

diminishes our appreciation of creation, dulls our responses, and may even

blind us to real insights.

Classical music buffs got excited in April 2003 when it was

reported that a Beethoven’s Ninth was going under the hammer at Sotheby’s. The

465 pages bound in three volumes may have been the manuscript used at the

premiere in 1824, the basis of the first printed edition in 1826. Beethoven’s

valued assistant Wenzel Schlemmer had died in 1825, and a number of other hands were

evident in the manuscript. ‘Du verfluchter Kerl’ (‘you damned fool’) Beethoven

wrote above the music at one point, ‘forgetting,’ as New York Times critic James R. Oestereich has pointed out, ‘universal

brotherhood [the theme of the last movement’s Ode to Joy] for an instant.’

There are changes to expression marks and various rethinkings, necessitating in

some cases the sewing in of whole new pages. There is even the odd coffee

stain, which goes to show that the creation of a masterpiece is a form of

industry; the result of labour, second thoughts, crossings out, the work of a

supervening genius, but also of a team of helpers who have to overcome the

hassles of everyday life to make a work of art which speaks beyond the ages.

We think of Beethoven as the supreme musical architect. But

in fact, Beethoven sat on the cusp of the period when composers turned from

improvisers into architects. Beethoven scholar Barry Cooper once likened

Beethoven’s manner of composition to finding one’s way along a wall which is

receding into fog in the distance and only becoming clearer as one gropes

along; and he contrasted this with the working method of Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), who described musical conception as a house becoming

clear in all its details at once. Beethoven’s way of composing seemed to offer

fewer guarantees of success; it is remarkable that he was able to make of his

pieces such integrated wholes. The fact that they are owed a lot to his galvanising genius.

So Beethoven would basically begin at the beginning - not as

common as you’d think. He’d map out the first movement, writing a sort of

synopsis of key moments (not particularly worrying about the joins), while

noting ideas for the movements ahead (and maybe other works). He would then

work on subsequent movements, filling in details behind him as ideas matured,

as understanding grew, while nudging a piece forward. With the Ninth, the very

first idea actually to be conceived (some time after the winter of 1815) was

for a fugue on a theme we now recognise as the main theme of the scherzo second

movement, the most popular movement at the work’s first performance. But not

long after that, Beethoven came up with something similar to the prophetic opening

to the symphony we now know. In the synopsis of the opening to the symphony

sketched by Beethoven in the winter of 1815/16, one sees the same doubtful

suggestion of A minor, and then the decisive landing on D minor; nebulousness

leading to decisiveness, a compositional expression of Beethoven’s customary

manner of working.

It was some time later that Beethoven got around to thinking

about the fourth movement. The famous choral finale may not have been

inevitable. One of Beethoven’s ideas around this time is rather like the last

movement of the String Quartet in A minor, Op.132 – but in D minor, the key of

the Ninth Symphony. Maybe a string-dominated Allegro appassionato was slated for this work. What a different

ending we would then have experienced, if this fast music [I’ve

roughly orchestrated it in a sub-Beethoven-type way] had followed upon the radiantly slow third

movement...

Audience reactions in the past 188

years may have been a few decibels lower on the applause-meter.

But Beethoven

also wrote under the 'instrumental' sketch of thsi passage the words ‘Before the Freude’, ‘Freude’ being the

first word of Schiller’s poem. Could he have been thinking, if not of a

completely instrumental last movement, of a different instrumental introduction

to the choral finale, before lighting on the brilliant idea of a choral finale

preceded by the now well-known 'horror fanfare' and ‘critical review’ of all the preceding movements?

Beethoven had been meaning to set Schiller’s ode To Joy to music for many years. There is

mention in a letter to Mrs Schiller dated 1793, over 30 years before the

premiere of the Ninth, that a young composer from the Rhineland, that is

Beethoven, was intending to set the poem. And in the sketchbooks dating from

1798 there is an early setting of the line ‘muss ein lieber Vater wohnen...’

(‘there must dwell a loving father...’), which Beethoven, back then, set to a

melody in C major.

Beethoven had of course written another Choral Fantasia, with an Ode-like

melody, not yet the perfect tune he honed for the Ninth, and based on a text in

praise of music. But why did it take him more than 30 years to finally set the

Schiller?

Political sensitivity? It is well known that Schiller had

substituted ‘Freude’ (joy) for ‘Freiheit’ (freedom) to evade the censors. But

there’s some justification for thinking that ‘Überm Sternenzelt muss ein lieber

Vater wohnen’ was the line that held most significance for Beethoven. ‘Be

enfolded, all ye millions, in this kiss of the whole world! Brothers, above the

canopy of stars must dwell a loving Father’.

This occurs as the first chorus in

Schiller’s version of the poem but Beethoven saves it for later. What he then puts

after the first and second verses is Schiller’s fourth chorus: ‘Joyously, as His

dazzling suns traverse the heavens, so, brothers, run your course, exultant, as

a hero claims victory.’ Beethoven thus edits and rearranges Schiller’s poem in

order to create a sequence that takes us effectively from earthly celebration,

to the hero who advances to the stars, to the benevolent maker (of us all?) who

must be beyond. Is this the real Beethoven, looking towards the open sky, like

the prisoners in his opera Fidelio,

newly freed from their dungeon cells?

And how would we describe the music for this passage? It is

a part of a mysterious adagio that the youthful Beethoven could not have

achieved. In his final setting of these words Beethoven makes use of sounds

that he discovered while working on certain sections of the Missa solemnis, new sounds intended

to depict something beyond the heavens, and inspire a sense of primal awe. It

seems that Beethoven’s final view of the ode To Joy had to wait until after the writing of the more

heavens-gazing sections of the great Mass in D. The significance of Beethoven

having to wait so long before setting Schiller’s poem relates, I think, to his

need to find an elevated view of the text, a more universal view.

But also more personal. Beethoven once said that music was a

higher revelation than religion or philosophy, but what is revealed by looking

behind the scenes at the Ninth? It's more than just an academic exercise. I draw on what

I’ve read of Beethoven’s abused childhood, think of the words ‘lieber Vater’,

and find great poignancy in Beethoven’s extension of a universal hope for

benevolent fathering in the slow section that precedes the tumult and applause-inducing excitement of the loud, prestissimo and oh-so familiar ending of Beethoven’s Ninth.

- first published by Symphony Services International. Reproduced by kind permission

If you are interested in reading other articles of mine on classical music, please see:

Sousa and the Sioux, 19 August 2011

Percy Grainger, the chap who "wanted to find the sagas everywhere", 17 June 2012

A Star and his Stripes - Bernstein, the populist, 29 June 2012

Igor in Oz: Stravinsky Downunder, 17 July 2012

Wagner - is it music or drama? 27 July 2012

"Beautiful...sad": Puccini's La boheme, 29 July 2012

Philippa - an opera [blog 1], idea for an opera on Philippa Duke Schuyler, 16 Sep 2012

No comments:

Post a Comment